From a CIA declassified document translating the "Latvian Legion" article contained in "Latvju enciklopēdija", published 1950–1955, Trīs zvaigznes, Stockholm. Legion in Courland from Wikipedia. Headings added.

Latvian partisans

After the 13–14 June 1941 deportations [of Latvians by Soviets], former officers and non-commissioned officers of the Latvian army, as well as former policemen and Aizsargi [national guard/army auxiliary] sought refuge in the forests; there, partisan units of various sizes were formed. Some of these units were sizeable—as for example, the one operating in the vicinity of Gulbene—and consisted of deserters from the territorial corps [following the invasion and annexation of Latvia by the USSR, the former Latvian army was included as a territorial corps in the Red Army]. The partisans attacked NKVD forces, and, after the beginning of the Russo-German war, also retreating units of the Red Army; thus, the Russian rear was made insecure, and their retreat speeded up. In such a manner, further deportations, robbing, and destruction of houses was avoided.

The partisans established contact with German army units; next to the German Kommandantura's the Latvians established also their own. In the beginning, the latter carried out all the tasks of the uniformed police. However, this collaboration ceased immediately after the arrival of German Sonderfuehrer's, Generalkommissar Drechsler, and the commanders of the SS police forces. The chief of the latter in July, 1941 abolished all Latvian units, forbade the wearing of Latvian uniforms, and ordered, on pain of death, all arms to be turned in. The Latvian Kommandantura's were reorganized: police prefectures were re-established in the cities of Riga, Daugavpils, and Liepaja, and district [police] chiefs were appointed.

Partisans disarmed, Eastern Front recruiting reserve established

Dno and Staraya Russa relative

Dno and Staraya Russa relativeto the Baltic states

The Germans formed a 500-man Rekrutierungsreserve, ostensibly for guarding important objects in Riga. These officially recognized Latvian companies were then united into the 16th Police Battalion. A verbal order was issued, to the effect that the battalion should be prepared to be sent to the front "to fight Bolshevism." Thereafter, two more battalions were formed, one in Riga and one in Liepaja. There was no lack of volunteers, since the people hated the Bolsheviks; the relatives of those deported and tortured to death in prisons during the Year of Horror [reference to Soviet occupation of Latvia in 1940-41] sought revenge. On 22 October 1941, the 16th Police Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Mangulis, was sent to the Eastern Front. Initially, its task was to guard the Dno–Staraya Russa railroad; however, soon one company and several platoons were assigned to German front-line units. Meanwhile, the formation of two additional battalions in Riga was ordered.

Satellite view of the Dno to Staraya Russa rail line today

Satellite view of the Dno to Staraya Russa rail line todayAdditional battalions established for the Eastern Front

On 16 February 1942, General Jeckeln, chief of the Ostland SS and police, ordered the formation of 11 additional Police Battalions. The Internal Affairs Directorate of the Latvian Local Authority [reference to Landeseigene Verwaltung, a Latvian agency with limited administrative powers] participated in this action through establishment of a "Chief Committee of the Latvian Volunteers Organization," headed by Gustavs Celmins. The Latvian police headquarters in Riga (located in Anna Street) supervised the formation of these battalions. These poorly trained and ill-equipped battalions were sent to distant sectors of the front, scattered through German army units from the Finnish Gulf to the Black Sea. Although nominally these battalions were under Latvian command, in practice, their actual commanders were German liaison officers.

Latv. kārtības dienesta bat. nosūtīšana uz fronti 1941 g.

Latv. kārtības dienesta bat. nosūtīšana uz fronti 1941 g.Latvian police battalion being sent to the front in 1941. at page 1289 Latv. Enc.

The flow of volunteers ebbed already during the second half of 1942, because Nazi activities in Latvia differed little from those of the Bolsheviks: the [Communist] nationalization decrees remained in force, persecution of Latvian patriots continued; as regards food, supplies, wages, and other rights, Latvians were considered to be on the level of the so-called "Eastern" peoples. The [Nazi] Party and civilian authorities did not hide the fact, that after the war the Baltic States would be colonized by Germans.

Additional battalions mobilized

Although the police battalions were formed for the ostensible purpose of securing order in Latvia, they were sent to Russia and were not released after the decreed one year of service. Until March, 1943, the formation of Latvian units was "voluntary;" in practice, this term had the same connotations as in the Bolshevik jargon. The German authorities decreed, that all aizsargi were to be subordinated to the police; they were named "Type C Auxiliary Police." They were first gathered together in each district; then, their ranks were augmented by policemen on independent duty in towns and the countryside; finally, it was announced, that for "training purposes" all were assigned to a police battalion. Many of the men mobilized in such a manner were ill and unfit for military duty. Including reserves, a total of 38 such battalions were formed in 1941-1944. Later, some of the battalions, decimated in battles, were united. 11 battalions were assigned to police regiments, and 9—to the Latvian Legion.

The Latvians for the first time went into battle as a closed unit in June, 1942, when the 21st Police Battalion (formed in Liepaja) went into action in the Leningrad front sector. The battalion, though ill-equipped and lacking anti-tank weapons, on 28 July 1942, after bitter fighting, repulsed a Red Army attack launched with strong artillery and tank support. Himmler, on a visit to the Leningrad front at the end of January, 1943, ordered that the international 2nd SS brigade (which included 2 Latvian police battalions) be reorganized into a Latvian brigade. These battalions (the 19th and 21st) which had valiantly fought in the preceding battles, in German staff reports were named as "belonging to Germanic peoples." The 21st battalion was directly subordinated to the commander of the Dutch legion. Both battalions were withdrawn from the front lines and transferred to the Krasnoye Selo region. On 4 February 1943, the 16th battalion, commanded by Maj. Kociņš, also was moved there. All three battalions were renamed: The 21st became the 1st battalion of the Latvian Legion [l/Lett. Legion], the 19th—the second battalion of the Latvian Legion [2/Lett. Legion], and the 16th—the 3rd battalion of the Latvian Legion [3/Lett. Legion].

Latvians informed of the establishment of the Legion

The Latvian Local Authority was officially informed about the establishment of the Latvian Legion only on 27 January 1943. On that day General Schroeder, chief of the SS and police in Latvia, invited for a meeting all General Directors [of the Local Authority], Col. Silgailis and Col. Veiss, as well as the Latvian Sport Chief R. Plume. Schroeder demanded, that the Latvian authorities aid in the voluntary formation of the Legion. On 29 January, another meeting was called—by Generalkommissar Drechsler. On this occasion, the Local Authority pointed out, that all efforts to gather volunteers would be fruitless, unless Germany gave the following guarantees: That the Legion would fight for a free and independent Latvia; that the properties [nationalized-by Soviets] would be re-privatized; and that the persecution of Latvian patriots would cease. As a result of the meeting, Drechsler decided to abolish the volunteer principle. In spite of this fact, on 10 February 1943, there followed an order signed by Hitler and Himmler (the text of which the Latvians obtained one year later), stating: "I order the establishment of a volunteer Latvian SS Legion. The size and structure of this unit is to depend on the number of Latvian-men available." According to some reports, Hitler had intended to set the strength of the Legion only at 10,000 men; however, Drechsler increased this number.

Illegal conscription commences

Immediately afterwards, the German authorities ordered all officers and NCO's of the former Latvian army to register in police precincts. An SS Ersatzkommando Ostland was established in Riga on orders of the Berlin general staff of the SS. Drechsler, on the basis of a 19 December 1941 decree by minister A. Rosenberg, on 23 February 1943 ordered all [Latvian] employment centers to call up for military service all men born between 1919 and 1924, a total of some 58,000. It was intended to divide this number as follows: 25,000 men were to be assigned to army auxiliaries [Hilfswillige, or HiWi's], 16-17,000 were to be included in the Legion, 10,000 in militarized labor units, and 6,000 to strengthen the police battalions. These were the first "full years" following the Latvian War of Liberation, which included the youth grown up during Latvia's independence [reference to increase in birth rate following World War I].

Such a proposed dispersal of Latvians among German units caused a wave of great unease in the nation and forced the Local Authority to agree to the formation of the Latvian Legion in order to at least partially secure Latvian interests. The Local Authority, after discussing the situation, on 23 February 1943 forwarded a memorandum to Reichskommissar Lohse, Drechsler, and Jeckeln. [The memorandum] pointed out the illegality of the proposed mobilization, and emphasized that the attitude of the Latvian authorities would depend on German acceptance of the following minimum demands:

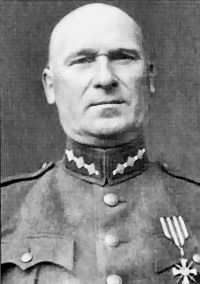

- General R. Bangerskis to be appointed as commander of the Legion, with Col. A. Silgailis as the chief of his staff,

- Each mobilized Latvian citizen, born 1919-24, to have the right to choose a particular type of service, without the use of compulsion,

- The Legion must undergo at least six months of training in Latvia. Only then is it to be put at the disposal—as a single, closed unit—of the German commander-in-chief,

- The Legion shall fight only in the Northern sector of the Eastern Front,

- The Legion is to receive the same food, provisions, clothing, pay, and rights existing in the German army.

German prevarication over Latvian demands

Knowing, that the people opposed the illegal mobilization, and not wishing that it suffer total failure, the Germans delayed their answer. On 2 March, it was announced, that General Hansen, empowered to settle the matter of the Legion, was to arrive from Berlin. The latter announced, that appointment of Bangerskis as commander of the Legion had been approved; yet, the appointment was delayed. On 20 March, it was found that Bangerskis had been appointed commander of only the 1st Division. Finally, on 31 March it became known that even this had been a misunderstanding—the divisional command would be German.

General Bangerskis was informed that he had been named Inspector General of the Legion; on 31 April [sic] 1943, Col. A. Plensners was appointed chief of his staff. Col. A. Silgailis became infantry commander of the 1st (German numeration, 15th) division [of the Legion]. In a special instruction it was promised to delineate the rights and duties of the Inspector General; this, however, never took place, and until the very end of the war his position in regard to representation of Latvian units, was quite unclear and restricted. General Bangerskis was indirectly subordinated to Himmler, and directly to Jeckeln. As formation of the Legion had already begun, and the Local Authority had already issued the corresponding appeals to the people, it now had no choice but to submit to these German directives. The tasks of the Inspector General were: Mobilization of citizens of Latvia (as of 15 November 1943); furthering national culture and ideological leadership of the Legion; inspection of Legion units; handling of funds donated to the Legion; supplementary aid to wounded and ill legionaries, and care of the relatives of those killed in action; representation of the interests of the Legion to the SS and German Army commands; supplementation of the Legion with officers, NCO's and medical personnel; in addition, as of 20 February 1945 he was also President of the National Committee.

Mobilization and deployment

As already stated, the first compulsory mobilization was ordered by German authorities. It was carried out by the following agencies: [Mobilization] for labor service and army auxiliaries—by the staff of the commander-in-chief, Ostland; for the Legion—by SS Ersatzkommando Ostland. On 26 March the Local Authority had empowered the leadership of the Legion to send out individual mobilization "orders,"; the employment administration boards could take steps against those who refused to obey. The men slated to serve in labor units and as HiWi's, were mobilized immediately, but mobilization for the Legion was delayed until late autumn, 1943; a part of the mobilized men were assigned to police battalions.

The [SS] Ersatzkommando [Ostland] ordered the draft boards to assign 25% of the men to the Legion; the rest were assigned individually to German units or police battalions. The 1919-1924 age group, totalling some 27,000—the army auxiliaries (Hiwi's)—was the most unprotected; they were scattered all over the Eastern front. The some 10,000 men assigned to labor units for the most part became HiWi's.

In a breach of promise, the Germans already on 30 March 1943 sent 1,000 Latvian youths to the Krasnoye Selo region; these, drafted only a few days previously, had no training whatsoever, and lacked Latvian officers and NCO's. They were the first supplement to the Latvian brigade forming there. The rest of the men assigned to the Legion, some 14,000 in number, were sent to Paplaka in Courland, where on 23 March 1943 the formation of the 1st Division was begun. Lack of housing and weapons (for example, in Paplaka at times there were 200 rifles per 1,800 recruits) greatly hindered the formation of the 1st Division. However, the chief obstacle was constituted by the fact, that the [division's] trained recruits were sent to the 2nd Brigade, which stood at the front. An 8 November 1943 order renamed the brigade "2. Lettische SS Freiwilligen Brigade;" and the 1st and 2nd Regiments were officially named the 42nd and 43rd [so-called] volunteer SS grenadier regiments.

Integration as combat units

The legionaries were required to take an oath, stating that in the struggle against Bolshevism they would unconditionally obey the supreme commander of the German army, i.e., Hitler. The weapons, clothing, and food of the Legion were comparable to that issued to German units. The legionaries wore the following insignia: Besides the insignia denoting rank (the ranks were those of the German SS), on their left sleeves were sewn badges in the colors of the Latvian national flag, topped by the inscription "Latvija." Instead of the SS collar insignia, members of the 15th Division (Latvian numeration, 1st) wore the Latvian rising sun emblem, and those of the 19th Division (Latvian numeration, 2nd), the Latvian fire cross emblem. Border guard units had black insignia. On the whole, pay corresponded to that prescribed by German army regulations. Each soldier received only combat pay (Wehrsold); the basic pay was sent directly to his family, or deposited in a bank account. Until October, 1944 the bank accounts were located in Riga, thereafter in Prague.

The medical personnel of the Legion consisted of Latvians. The wounded and sick soldiers convalesced, for the most part, in Latvia. The Latvian trade unions donated 50,000 Reichsmarks and 250 beds to the Legion, enabling the establishment of a first-class Latvian Legion hospital in Riga on 13 December 1943. In the fall of 1944, it was evacuated to Germany—first to Mecklenburg (in Schwerin), then to Luebeck; there, renamed Latvian Hospital, it continued to serve Latvian refugees and invalids as late as 1951.

Dankers “role”

Pursuant to a 1 May 1943 order of [General] Dankers, the Latvian Soldiers Aid (LSA) was set up. Its chief was Bruno Pavasars, the secretary general—Evalds Andersons. The task of this organization was to further the national culture. It financed the Legion's official newspaper Daugavas Vanagi [The Falcons of Daugava], provided a front-line theater, established rest homes, collected gift parcels (75,000 were collected in Christmas, 1943 alone), provided for supplementary care of the wounded and the sick, etc. Many other Latvian establishments, organizations, and individuals were engaged in similar work. LSA acquired its funds from donations and from revenues of various events.

Bruno Pavasars, photo at www.mfa.gov.lv

Bruno Pavasars, photo at www.mfa.gov.lvSoldiers of the Latvian units were subordinated to German courts. A military court, headed by the divisional commander, was attached to each Latvian division. Where these courts did not exist, the accused were tried by the 16th SS and police court in Riga. Legionaries whose sentences exceeded 3 months imprisonment were sent to the Salaspils concentration camp, administered by Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Berlin. Those receiving light sentences were assigned to a special punishment company stationed in Jelgava, but—as of 1944—to a special punishment battalion in Bolderaja (the so-called "Captain Meier's battalion"). The men arrested and held for court-martial were incarcerated in the Riga Central Prison (a total of some 500 men), or in the army prison in Riga.

Progression of mobilizations

[There should be no inference that the Germans were not in total control. — Ed.]

Bangerskis — quasi head of forces

A new stage in the formation of the Legion was officially inaugurated on 15 November 1943. General Dankers announced to a large assembly of Latvians gathered in the great hall of the University of Latvia in Riga, that henceforth the Local Authority would itself mobilize citizens of Latvia, under the draft regulations of independent Latvia; General Bangerskis would thus exercise the powers of Minister of War and Commander-in-chief of the Army [as outlined in the constitution of independent Latvia]. Since the Local Authority was not a government, but only an auxiliary organ to the German civil authorities, then its announced mobilizations were just as illegal as the previous one. A special military court, headed by Gen. Bangerskis, was established to try draft-dodgers. Bangerskis also confirmed the verdict of the court, and could reduce or cancel sentences. This military court operated according to the regulations governing proceedings of military courts of [independent] Latvia.

By July 1944, the situation at the front was critical. Therefore, Jeckeln agreed to Bangerskis' proposal to free the soldiers interned in the Salaspils concentration camp, as well as those serving lighter sentences in prisons. From these Latvians, 6 construction battalions were formed; Captain Meier's battalion constituted the seventh. After their formation the battalions were placed at the disposal of the chief of Corps of Engineers. However, due to numerous desertions, the number of men serving in them rapidly decreased. It should also be noted, that in 1943 the Germans had formed two construction battalions from mobilized Latvian HiWi's.

Dankers — quasi head of mobilization

Already on 29 November 1943, General Dankers, General Director for Internal Affairs [of the Latvian Local Authority] ordered the mobilization of all former Latvian army officers and NCO's, as well as the men born between 1915 and 1924. In January 1944, with the retreat of the German 16th and 18th armies from Leningrad, fear arose of a possible Red Army invasion of Latvia. In order to avert this danger, the Local Authority decided to form 6 border guard regiments. For this purpose, Dankers' 2 February 1944 order mobilized—the men born 1910-1914, and that of 5 February 1944—the men born 1906-1909. However, already during the second half of March and the beginning of April, three of these regiments (1st, 2nd, 3rd) were sent to the front and placed at the disposal of the VI SS Corps; meanwhile, a new 2nd regiment was formed [in Latvia]. The men living near the Latvian–Russian border, being politically unreliable, were assigned to 2 construction battalions; the battalions were placed at the disposal of the commander of the Corps of Engineers. The remaining 4 [border guard] regiments were in training; however, already on 16 April the 2nd Regiment was sent to the front in the Drisa region [near the Latvian–Russian border]. The other regiments went into action in the beginning of July in the vicinity of Daugavpils. There, they suffered heavy losses. The regiments then were withdrawn from the front. The 2nd and 5th regiments were merged into a single regiment, the 7th; this unit, renamed the 106th grenadier regiment, then was assigned to the VI SS Corps. The remnants of the remaining 2 [border guard] regiments were either assigned to the 19th Division [of the Latvian Legion], or sent to Germany.

Mobilizations target the poor and unfit

On 14 February 1944, Jeckeln liquidated SS Ersatzkommando Ostland. It was replaced by SS Ersatzkommando Lettland with Bangerskis as chief. However, actual direction of the mobilization remained in German hands. Bangerskis repeatedly protested to Jeckeln and Drechsler, pointing out the illegal and disorderly acts which the German authorities committed by the virtue of their position and the incorrect mobilization systems; the aim of these [Germans] was to reduce the authority of the Inspector General. In the course of mobilizing the men born between 1915 and 1924, only 3,500 out of a total of 9,200 were assigned to the Legion; the rest had either not registered, or received the so-called "UK cards," which exempted one from military service. Therefore, on 18 March 1944 Bangerskis forwarded the following memorandum to Jeckeln: "It is well known, that the recent mobilization of men born between 1910 and 1924 has created much unrest. The orders of the various German institutions, exempting a number of enterprises from the mobilization, created a situation where the employers themselves decided which employees 'were to receive UK cards and which ones weren't; thus, they could exempt their friends and relatives. As a result of such measures, in the countryside, the land proprietors were exempted, and the workers and the poor were mobilized." In a 21 March 1944 meeting Jeckeln admitted, that bribery had existed in the district draft boards, and that only the poor had been mobilized. Bangerskis then pointed out, that if only 32,000 men were to be mobilized, it had been unnecessary to require 120,000 to register; the boards could thus draft only every fourth individual—and the decision was entirely up to them [which one]. The Inspector General received bitter letters, pointing out, that "instead of youths, pieces of bacon were mobilized." As the results of the mobilization of the men born between 1906 and 1924 (totals 181,439) came in on 10 June 1944, it turned out, that a total of 43,223 men—serving in the police, as prison guards, border guards, or in the railroad service—had either not been required to register, or had received exemptions. Mobilization was postponed for 50,500 of the men examined; 18,772 were judged unfit for military duty; 23,000 were assigned reserve status; some 7,000 were given sick leave; and 4,774 were turned over to doctors for further examination. Thus, this mobilization gave only 34,000 men for active service.

In order to augment the ranks of the 15th Division, Dankers on 21 June 1944 ordered all men born in 1925 and 1926 to be mobilized; in addition, towards the end of that summer, youths and students born in 1927 and 1928 were mobilized. The latter measure the Germans had already demanded previously. The agencies holding joint responsibility for the last-mentioned mobilization were the German aviation commission and the Latvian Youth Organization; the youths were assigned to German, anti-aircraft and searchlight units. At the time of the German surrender, there were some 600 such "air force auxiliaries" in the city of Liepaja (Courland) alone. Approximately 2,500 were sent to Germany, where they were taken prisoner. The Germans suffered great manpower losses in the summer of 1944. Subsequently, all [Latvian] ground crews of airfields were placed at the disposal of the Germans; they were replaced by non-combatants and persons judged able to work (the so-called "av" category); Jeckeln demanded that the Local Authority assign to air force auxiliaries all the men born between 1909 and 1926 who held either draft status mentioned [in the previous sentence]. After extended talks, Dankers yielded, and issued the necessary mobilization order in August 1944. These draftees were either sent to Germany to serve as airfield crews, or assigned to German parachute units. A part of the Latvian "air force auxiliaries" were sent to various air-fields in Italy; there, they eventually became prisoners of war and for the most part returned [to Soviet-occupied Latvia] after the war.

Aviation unit

In September 1943, the Germans began to form a Latvian aviation unit named ENO, and established fighter pilot schools in Liepaja and Grobina (Estonian pilots were trained there also). The 3-month long training program began in October, 1943.1 All former Latvian Army Air Corps pilots, as well as those of the Aizsargi and civil aviation, were assigned to ENO. This organization also accepted students from technical and trade schools. Altogether, three classes were graduated; from these, two night fighter squadrons, each having 18 planes, were formed. In September 1944, the 1st and 2nd night fighter squadrons were merged into the night fighter group no. 12, and that unit received the name Aviation Legion "Latvija." Its task was to conduct low-level operations in the immediate rear of the enemy. Lieut.-col. Rucelis was named commander of the Aviation Legion. However, already on 27 September 1944 the Aviation Legion was transferred to Stettin. The planes were taken away, and the men sent to Denmark for parachute training. Nothing came of this. In December 1944, the Latvian flyers were transferred to Koenigsberg for antiaircraft training. There, in January of 1945, they were captured by the Russians.

Training and reserve unit

Concurrently with formation of the 15th Division [of the Latvian Legion], a training and reserve unit for it was also set up. It was located in Cekule (near Riga) under the command of Lt.-Col. Jansons. Later, it was transferred to Jelgava and renamed the 15th Training and Reserve Battalion. Its sole task was to take care of convalescing legionaries. When the 15th Division left for the front, the battalion was responsible for providing replacements for both divisions [of the Latvian Legion]. In beginning of 1944, the battalion was enlarged into a brigade. Its commander was a German and it consisted of 19 units. In July I944, during the sudden Red Army attack on Jelgava, these units were thrown into battle at Janiski, Lithuania, and lacking weapons, suffered heavy losses and were completely scattered. The remnants were transferred to Berendt, East Prussia, where a new 15th SS Grenadier Training Battalion was formed. Its task again was to retrain convalescing legionaries. Towards the end of January, 1945 this unit was sent to the Danzig region, where, like the other units of the 15th Division left, in that particular area, it was captured by the Russians.

When the Red Army reached the Baltic Seavat Memel (September, 1944), Latvian police units and remnants of other units of a military nature were sent to Germany and placed at the disposal of the 15th Division. Among these men there were many who due to age or health were unfit for front-line duty; therefore, they were assigned to construction units. A total of 3 construction regiments were formed. At the end of 1944, the SS command unified them into the Latvian Field Replacement Depot, whose commander, as well as all of the staff, were Germans. The task of this unit was to gather all Latvian police employees and members of military units sent to Germany. After examinations by doctors, a part of these men were sent to the front; the majority, however, were detailed to construct fortifications. These were the so-called "ditch diggers of Torn." In the beginning of 1945, the 1st and 2nd construction regiments were working in the Torn region, the 3rd—North of Neustettin. The food, clothing, and weapons these men were supplied with was of exceptionally poor quality. This created much bitterness. The soldiers were not even provided with housing. Towards the end of January, 1945, with the Red Army approaching West Prussia, these units retreated westward. The retreat became a catastrophe. The men were completely unarmed, without food, and without transportation. Russian tank columns several times cut the roads, scattering the [Latvian] units and causing them considerable losses. However, most of the men succeeded in avoiding capture, and reached Stettin in the beginning of March; there, they again were put to work digging trenches. In the second half of March, the so-called "Captain Rusmanis' group" (2,500 men) was sent back to Kurzeme [Latvia]. At the end of April, with the Red Army approaching Stettin, the construction units again retreated westward. This time also, Russian tanks cut the retreat routes several times, taking prisoners and causing losses to the units. In the beginning of Kay 1945, the remnants of these units surrendered to the British and Americans near Wismar.

Himmler's original order

Himmler, in an order issued on 24 May 1943, specified that the term "Latvian Legion" was to be a comprehensive denomination for all Latvian units serving in the Waffen-SS and police forces. Therefore, Latvian battalions which previously had been called gendarmerie, were renamed Latvian Police Battalions. The formation and training of these battalions since 1942 was entrusted to Lt.-Col. R. Osis, whose chief of staff until November of 1942 was Lt.-Col. K. Lobe. The volunteers had to sign a contract for one year of service.

In addition, the order by Himmler just mentioned contained the following provisions: a) Major Gen. von Scholz was appointed commander of the 2nd Latvian SS brigade; b) Count von Pueckler was appointed commander of the 15th Latvian SS division; c) henceforth, Latvian soldiers were to be decorated with German medals instead of the Ostmedaille; these were to be awarded by Jeckeln. Himmler also issued an order authorizing the sending of the Latvian police battalions to the front. As already mentioned, at first there were 30 such battalions together, they were equal to one infantry division. They were scattered all along the Eastern Front, from Leningrad to the Black Sea. Poorly trained and ill-armed, they were thrown into battle not only against the regular Russian army, but also against partisans in Lithuania, Poland, Belorussia and the Ukraine; they were also utilized to guard POW camps. Repeated protests by Bangerskis were of no avail. On 1 August 1943, four of the police battalions were united to form the 1st (Riga) Police Regiment; its commander was Lt.-Col. Meija. Since December 1942, these 4 battalions, containing many old and sick men, had lost 683 men; the regiment had only 42 officers and 980 men. Only in March 1944, was this regiment withdrawn from the front and sent back to Latvia. In addition, in the beginning of February 1944, the 2nd and 3rd Police regiments were also formed. All three regiments were thrown into battle in July 1944 in the Daugavpils region. They suffered heavy losses. In the course of the fighting, one regiment was surrounded in the Vilnius area. Breaking out, it was decimated: When on 16 August 1944 the battalion arrived in Riga, it contained only 5 officers, one doctor, and 42 men. After the retreat from Daugavpils the [police] regiments were stationed in Bulduri. In the second half of August, all three regiments were merged. In October, this unit was transferred, first of all to Dundaga, then to Germany, where it joined the Latvian Field Replacement Depot.

Subordination to Wehrmacht command

The Latvian Legion was subordinated to the VI SS Corps, the leadership of which, with the exception of 1-2 Latvian interpreters, was German. The commanders of both Latvian divisions were also Germans; however, the divisional infantry commanders were Latvians (15th Division—Col. Arturs Silgailis; 19th Division—Col. Voldemars Veiss, later Col. Karlis Lobe). They were the highest service commanders of all Latvian soldiers, and therewith, advisers of the divisional commanders in questions of national welfare [Comment: untranslatable—meaning of term can also include culture and ideology] +and training. During battles, the infantry commanders were entrusted with operative leadership of various battle groups. They also had a small staff, consisting of 2 officers and several clerks.

The German command of the Latvian divisions attempted, as much as possible, to ignore the infantry commanders. From the regimental level down, all leadership was in Latvian hands; however, at first each police battalion, construction battalion, and frontier guard regiment had a German liaison officer attached to it. These usually considered themselves to be the direct superiors of the Latvians. Such a situation caused numerous incidents, which sometimes ended with the Latvian officers' being relieved of command, and even with their being court-martialed. Thus, Capt. Praudins, commander of the 19th Police Battalion, was sentenced to death, ostensibly for having committed acts hostile to the Germans.

Bangerskis, in a 21 March 1944 meeting with Jeckeln, protested that the Latvian frontier guards, minus their officers and NCO's, had been sent to Poland to fight guerrillas. The position of the Inspector General was, to say the least, unenviable; often he could not even inspect the regiments. The Latvian regimental commanders were forbidden to give official reports to Bangerskis; they could only contact him privately.

The Latvian Legion in combat

Russia

In April 1943, all three police battalions were located in the Krasnoye Selo region, where they were merged into the 1st Latvian Infantry Regiment; its commander was Col. Veiss. Col. Lobe, who arrived there shortly afterwards, began to form the 2nd Latvian Infantry Regiment (nicknamed the "Imanta" regiment). To form the latter, the 13th, 24th, and 26th [Latvian] Police battalions were merged (it should be noted, that the 18th battalion was only sent to the regiment in June 1943, when the regiment already held a sector of the front near Volkhov). Simultaneously with the infantry, Capt. Gravelis began to form the artillery section. Formation of other units was also begun.

After a month of training, the brigade was sent to the Volkhov front sector, to hold the position Terenitse Kurlyandskaya–Spaskaya Polist. This position was in a swampy vicinity and was almost completely unfortified. Within a short period of time, our soldiers transformed it into an exceptional fortified position. The brigade made several local attacks, the biggest of which was the 3 September 1943 assault on the Spaskaya Polist hill, designed to improve the battle line. The assault was successful and our losses small. Because of the great tactical importance of the hill, the Russians attempted to recapture it during the following days. In the heavy fighting that followed, the brigade, despite considerable losses, retained the hill. As of 5 October 1943, the brigade was commanded by Schuldt.

In 1944, the Russians began their great offensive in the Leningrad front. On 14 January, they broke through the German front some 4-5 km south of the positions of the 2nd Brigade. The enemy planned to encircle the German forces which stood in the Volkhov front sector south of Lake Ladoga. In order to relieve the pressure on those German units engaged at the site of the breakthrough, the brigade formed a battle group, consisting of 1st Battalion of the 1st Regiment (commander, Capt. Jansons), and the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment (commander, Maj. Stipnieks). Its task was to attack the enemy flank . from the North. The battle group, commanded by Col. Veiss, successfully carried out the assigned task, freeing a corridor through which two surrounded German divisions could retreat. The battle group had to fight particularly bitterly near Kekochov on 17 January 1944. Col. Veiss, for his courageous and able leadership, was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross—the first Latvian to receive that decoration.

Due to the generally deteriorating situation on the Northern Front, the 2nd Brigade, on 19 January 1944, had to leave the positions it had built with difficulty and defended with gallantry, and to begin to retreat southeast, towards Gorenko. The retreat took place in great cold, deep snow, through a swampy and roadless region. Finding it impossible to break through towards Gorenko, the brigade changed directions and turned towards Pinev-Luga, where it took up a defensive position in the Gusi-Pyatiletsy region, some 10 km south of Pinev-Luga. This position was defended until 31 January. On 1 February the brigade retreated further southwest, through Orodezh and Bol'shie Sokol'niki. On 7 February, the brigade attacked Velasheva Gora, in order to lessen enemy pressure on the neighboring division. Having accomplished this task, the brigade during the following days retreated through Dubrovka - Antipov - Mal. Utorgosh - Podubyi - Romanovichi to Pskov. During this time (19 January to 25 February 1944), the brigade was incessantly battling both the advancing enemy and partisans, who attempted to block its retreat. During the heavy fighting near Zabolotye, the brigade lost Capt. Skrauja and Capt. Grants, commanders of the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Regiment. From Pskov, the brigade was transferred to positions on the river Velikaya, where it was ordered to hold a section of front next to and immediately north of the 15th Latvian Division.

The 15th Division, the formation of which had already begun on 23 March 1943, was sent to the front in mid-Novembcr 1943. The Division contained the following units [Comment: Latvian numeration]: The 3rd Infantry Regiment (CO, Col. Kripens), the 4th Infantry Regiment (CO, Col. Janums), the 5th Infantry Regiment (CO, Col. Apsitis), the 1st Artillery Regiment (CO, Col. Skaistlauks), the 15th Fusilier Battalion (CO, Capt. Lapainis), the 15th Sapper Battalion (CO, Capt. Klavins), the 15th Antitank Battalion (CO, Capt. Trezins), the 15th Antiaircraft section (CO, Capt. Bergs), the 15th Liaison Battalion (CO, Dostmann), and the 15th Field Reserve Battalion (CO, Maj. Smits). Many units were undermanned by as much as 25 percent. The regiments had only 2 battalions each. The 1,500 recruits of the 3rd Regiment had had only two weeks' training. Units of the division received their battle equipment only a few days before leaving for the front, or even on the very day (as for example, the 5th Regiment). There were either no boots, or they turned out to be too small. There was a shortage of horses, cars, and other equipment. The reason for such hurry was the Russian breakthrough at Nevel; the German army command had already in November 1943, decided to withdraw also the Northern front to previously prepared positions on the river Velikaya. Due to a lack of reserves, the 15th Division was ordered to defend those positions. After their arrival at Novo Sokol'niki, the Latvian units were ordered to continue training and to finish construction of defensive fortifications in the rear. In order to give the new soldiers battle experience, small groups of them were assigned to German front-line units in a rotating order. When in January began the Russian offensive, these Latvian soldiers were thrown into battle and thus were lost to the Division. The same must be said about the soldiers engaged in constructing fortifications; they, too, were drawn into rear-guard action. All protests by the Latvian commanders about such dispersal of Latvian units were of no avail. Even more—during the continuing battles, the 15th Division was repeatedly forced to send individual units to German divisions. For example, the 1st Battalion of the 5th Division was assigned, to the 69th German division, and the 2nd Battalion—to the 83rd German division. Moreover, the 2nd Battalion was broken up into companies: One company was assigned to the 457th German infantry regiment, two more—to the 275th regiment; finally, the last company was split into squads and assigned to various German units. The Latvian regimental commander and his staff remained in the rear with nothing to do; the battalion staffs also could not command their companies, and thus they likewise had no tasks which to fulfill. The Germans also took the light and heavy machine guns belonging to the men of the 15th Division which had been killed or wounded.

Finally, in the beginning of February, 1944, the 15th Division was ordered to proceed to the Belebel'ka region, some 45 km southwest of Staraya Rusa, and to take up positions on the river Redya. On the way to the Loknya railroad station, where the Division was to board trains, the 1st Battalion of the 3rd Regiment, and a part of the 15th Fusilier Battalion were suddenly [taken from the main body of troops and] thrown into battle in order to liquidate a Russian breakthrough. The battle lasted from 5-10 February, at which time the breach was contained and the Division could resume its march to the Loknya railroad station unmolested. In this battle the Latvian units were led by col. Kripens.

The sector assigned to the Division was approximately 30 km wide; due to such width, the Division's right flank consisted of a number of defensive points, with spaces in between. The Russians utilized this fact. During the night of 14/15 February 1944, under cover of a snowstorm, one of their ski battalions, and the 638th Russian Assault Regiment (totaling some 400 men), crossed our battle line south of Sokolye, at a location where the distance between our defensive points was 3 km. Having spent the day in the depths of the forest, the Russians on the night of 16/17 February attacked a point in our line simultaneously from the front and from the rear. The attack was directed against the junction of the 4th Regiment and the 15th Fusilier Battalion; therefore, the inner flanks of these units soon found themselves in a very dangerous position. Local reserves, organized by a regimental commander, counterattacked successfully. The Russians in our rear were encircled, and, after a battle lasting until the evening of 18 February, almost completely annihilated; only some 30 were taken prisoner.

However, the 15th Division did not long remain in this position. Already on 17 February it was ordered to start retreating (during the night of 20/21 February) to the so-called "Panther line" positions on the western bank of the river Velikaya. On that day the Division's commander, general von Pueckler-Burghaus, was replaced by the police officer Heilmann, a timorous man with little knowledge of military matters. Since the Division's route of retreat led through a swampy area, it was decided to utilize the single usable road Beiebel'ka - Dedovichi. The 4th Regiment and a company of the 1st Sapper Battalion, on the other hand, had to secure the Division's main column from the South; thus, it had to proceed westward in a separate column, straight through 70 km of swamps and forests. The retreat succeeded as planned. On 21 February, the Division's main column reached Aleksino, 30 km south of Dedovichi. On 22 February, the 15th Division was ordered to speed up the pace of the retreat. Since artillery and motorized units could not proceed in the direction indicated, they made a forced march along the Belebel'ka-Dedovichi road and then through Novorzhev to the river Velikaya. The rest of the Division reached its destination on 28 February, after 6 days of extremely difficult marches in great cold and snowstorms, through forests 30 km deep, finding directions often by compass alone, threatened by the advancing Red Army and partisans. The 3rd Regiment, which covered the Division's rear, had to also beat off repeated enemy attacks.

Due to a technical difficulty, the radio did not work; thus, it was impossible to relay the order about increasing the pace of the retreat to Col. Janums group [i.e., the 4th Regiment, proceeding separately]. Attempts to establish contacts with its patrols failed; they were destroyed by partisans. Meanwhile, Col. Janums' battle group, having beat off partisan attacks, reached the river Polisto only on 22 February, after a difficult cross-country march. Having received no orders, Col. Janums on the morning of 25 February continued to retreat along a country road. At this time, it became apparent that the battle group was surrounded deep within the rear of the enemy. In the afternoon of 26 February, in the village of Buligina, Col. Janums ordered his men to prepare for a breakthrough. All equipment—except weapons, ammunition, and food—was discarded. Avoiding roads and finding directions by compass, the group first headed due South, then West, through primieval forests. Already at the beginning of this march it was attacked by Russian cavalry; all vehicles were destroyed. Under cover of darkness, our exhausted soldiers during the night of 26/27 February broke through the envelopment and reached German lines near Novorzhev at noon of the 27th.

After their arrival in the "Panther line," the 2nd Brigade and the 15th Division were subordinated to the VI SS Corps, commanded by the Police General von Pfeffer-Wildenbruch. The assigned line of defense was 22 km wide. The line began at Voronichi, then went along the southern shore of the river Sorota until its junction with the river Velikaya, then along the western shore of Velikaya to Terekhov. The right flank of this position was defended by the 15th Division, the left—by the 2nd Brigade. Tactically, the position was ill-chosen: The western bank of Velikaya was much lower than the eastern bank; thus, the enemy could see deep within our rear and command it with his fire. Following a proposal of col. Veiss, it was decided to move the line of defense to the heights of the eastern bank. This could be done only opposite the position occupied by the 15th Division and the 2nd Brigade, since only here the Russians were yet not in close contact with the line of defense. Of course, this action was immediately followed by determined enemy counterattacks. A bitter and prolonged struggle, lasting from 4 to 19 March 1944, now began; it was started by a Russian attack on the Seredniye-Slepnyi village. One of the most bitter battles took place from 16-19 March, for possession of hill 93,4. The hill, on the eastern bank of Velikaya, commanded the entire river valley in the 2nd Brigade sector; if the hill were lost, the entire position on the eastern bank of Velikaya would have been endangered. During the three-day battle the hill changed hands several times. Finally, in the evening of 18 March, after a counterattack supported by German assault guns and bombers, it remained decisively in our hands. This was the only battle in the entire war, when both big Latvian units fought jointly and under Latvian command; in their sector, the Russians utilized 11 divisions.

During this time, the right flank and center of the 15th Division was not engaged in any large-scale battles; however, reconnaisances in force did take place. In this respect, the most successful were attacks by the 4th Regiment near Zhelezov (13 March) and Sizovka (14 March). Here, the first reinforcements arrived from Latvia, and our units could partly replenish the gaps in their ranks. The units which had been left attached to German formations near Novo Sokol'niki, also arrived. In mid-March, the 6th Regiment 2nd Brigade was assigned and was renamed the 19th Division.

Now, the Latvian units were named as follows: 15. Waffen-Grenadier Division der SS (Latvian no. 1), and 19. Waffen-Grenadier Division der SS (Latvian no. 2). The regiments of the 19th Division were named 42. Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS (Latvian numeration: 1st Regiment), 43. Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS (Latvian numeration: 2nd Regiment), and 44. Waffen-Grenadier Regiment der SS (Latvian numeration: 6th Regiment). The 1st Regiment was commanded by Maj. Galdins, the 2nd—by Col. Lobe, and the 3rd—by Lt.-Col. Kocins. Col. Veiss was named the infantry commander of the 19th Division.

On 15 March Schuldt, the commander of the 19th Division, was killed in action. The command was temporarily taken over by Bock; finally, on 13 April 1944 generalleutnant Streckenbach assumed permanent command. In view of our past manpower losses, the three recently formed Latvian frontier guard regiments were placed at the disposal of the VI SS Corps during the second half of March. The men of the 1st and 2nd Frontier Guard Regiments were used to replenish the ranks of the 15th and 19th Divisions; the 3rd Frontier Guard Regiment, together with the 15th Field Replacement Battalion, were placed in villages near Krasnoye (some 18 km East of the Latvian border), thus setting up something like a training and replacement center.

During the second half of March, 1944 it became known that the Russians were gathering forces for an offensive. On the morning of 26 March, they opened a very heavy artillery barrage on our positions along the river Velikaya. In a short space of time all of our heavy weapons had been destroyed. Around 7:30 AM the enemy attack began; it was directed mainly against the 5th Regiment. Having crossed the frozen river, the Russians already before noon had achieved a deep salient, reaching up to the regimental headquarters at Strezhnevo. This breakthrough was then, rapidly widened towards Southwest and South. Therefore, the 4th Regiment, which defended a sector South of the river Sorota, was forced to withdraw its left flank and to take up positions on the eastern bank of the river Velikaya. The 3rd Regiment, since it stood to the left of the 4th Regiment, was also obliged to withdraw its right-flank. Counterattacks, in which besides some units of the 4th Regiment and the 15th Fusiliers Battalion, also some German units took part, succeeded (with help of assault guns, and support aircraft) in stopping the Russians; however, the former positions could not be regained. When darkness fell, the battle died down. The enemy held a 3 km deep and 4 km wide bridgehead on the western bank of the river [Velikaya]. All Russian attempts to enlarge it during the following day were unsuccessful; so were also the German efforts to regain it. As the 15th Division had suffered heavy losses during the battle, it was replaced by German units (with exception of the 4th Regiment, which remained in position until 16 April, at which time it was transferred to Bardovo). The [4th] Regiment defeated several Russian attempts to cross the river Sorota, taking enemy prisoners and equipment.

Unable to increase their bridgehead towards Southwest and South, the Russians increased pressure against the right flank of the 19th Division. To defeat their attack, it was necessary to call in the 3rd Regiment (just withdrawn from the battleline) and some German units. During the attack of 7 April 1944, Col. Veiss was mortally wounded. He died in Riga on 16 April.

A second powerful Russian thrust, aimed at enlarging their bridgehead towards Northwest, took place on 11 April. After 30 minutes of very heavy artillery fire, the enemy attacked on a 2 km wide front running from Telechino to Aluferovo. The German units holding this sector began to retreat in disorder. The situation was saved only by a counterattack of our 2nd Regiment. In spite of their numerical superiority, the Russians were forced to retreat. When darkness fell, our previous positions had been largely regained, with exception of the Novyy Put' heights, which proved impossible to regain. After this engagement, there were no major operations in the sector held by the 19th Division for the time being.

During the second half of April 1944, the VI SS Corps was gradually transferred to the so-called Bardovo-Kudevere positions, some 50 km East of Opochka. As the spring thaw had begun, the transfer was difficult to accomplish. The sector which the corps had to defend was about 46 km wide; out of that distance, lakes constituted 20 km. The right flank (the so-called Bardovo position) was defended by the 15th Division; the left (the so-called Kudevere position)—by the 19th Division. As the Russians were not too active in this sector, both Divisions began intensive training; various courses were organized. In addition, formation of the 2nd Artillery Regiment [attached to the 19th Division] was begun; the rest of our artillery units were at this time being formed in Vainode [Latvia]. In the middle of May 1944, Col. Plensners (transferred from the staff of the Inspector General to the front by order of Jeckeln) took over the command of the 2nd Regiment; its former commander, Col. Lobe, was named infantry commander of the 19th Division. Col. Silgailis replaced Col. Plensners as the chief of staff of [Inspector General] Bangerskis.

The quiet period in the VI SS Corps sector was suddenly shattered by a Russian assault on height 228,4, lying in the extreme right flank of the 15th Division, and which was later nicknamed "Jani Hill." At 8 AM on 22 June 1944, the enemy opened a heavy artillery barrage against the hill, defended by the 3rd Regiment, and stormed it. Counterattacks, made with regimental reserves, were unsuccessful. Further attempts by the 15th Division, utilizing the 5th Regiment, the 15th Fusiliers Battalion, and units of the German 23rd Division, were likewise unsuccessful; the heights could not be regained. On 26 June, the Russians even managed to extend the breach.somewhat, surrounding the 3rd Regiment and some units of the 5th Regiment. How¬ever, our surrounded forces broke out during the night, suffering only small losses. This battle had brought about a conflict between Col. Kripens, (commander of the 3rd Regiment) and divisional commander Heilmann. Kripens requested that he be relieved of command. The request was granted, and on 26 June Lt.-Col. Aperats took over command of the regiment.

Towards the end of June 1944, superior Russian forces, supported by artillery, attacked height 261,1 (the so-called "Gruzdova height") in the 19th Division's sector. Their attacks were repulsed. On 22 June 1944, the Russians began a general offensive in the Vitebsk region, which resulted in the German line being broken through. In the beginning of July, the Red Army was rapidly approaching Vilnius; therefore, the German command was forced to pull back also their forces east of Opochka. On 9 July, preparations for the retreat began; our service organs, transports, and ammunition reserves were being pulled back. The Russians, whose observation planes often flew over our rear, found this out (or, partisans operating in the German rear could have given the Russians that information). On the morning of 10 July 1944, the Russians opened a concentrated barrage by artillery, mortars, and antitank weapons on a broad front; the fire was chiefly directed against the main roads [in our rear]. Many of our heavy weapons were destroyed before they could begin to return the fire. Thus, when the enemy, supported by tanks, began his assault, our troops began to retreat in a number of locations. The few rounds remaining for our weapons meant that the enemy could not be fought successfully. Regimental and battalion commanders hurriedly attempted to organize resistance in the lines to which the troops were supposed to have retreated, and tried to halt the Russian assault by counterthrusts. These attempts were frustrated by pincer movements of Russian tank forces.

There were many dramatic moments in the course of the Corps' retreat. The brunt of the enemy attack on 10 July was borne by the right wing of the 4th Regiment, holding a sector North of lake Ostriye. Here, Russian tank columns had penetrated deep into our positions. The tanks threatened to outflank us towards the Southwest (in the direction of Krasnoye), and to cut the single route of retreat for the units of the 15th Division (3rd Regiment, 5th Regiment, 15th Fusiliers Battalion), standing South of the lake just mentioned. These units were also threatened by Russian tank forces which had penetrated into the sector held by the German 23rd Division, and were approaching Krasnoye from the Southeast. However, our units managed to retreat behind the river Alolya; that this could be done, was partly due to a counterattack by the 34rd Regiment, and partly to Russian losses and fatigue.

In the 19th Division's sector, the brunt of the Red Army's attack was directed against the 1st Regiment, i.e., immediately North of lake Kudevere. Already at noon the Russians had penetrated 3 km into our lines and reached our artillery positions; there, they were halted by concentrated artillery fire, and our units were thus permitted to retreat. The defense was also aided by a heavy fog. In the sector held by the 2nd and the 6th Regiments (South of the lake), our lines held; the only exception was the extreme right wing of the 6th Regiment, where the Russians managed to break through and imperil that regiment's right flank.

Despite the disorganisation caused by the general Russian offensive, both divisions retreated without being surrounded, and early in the morning of 11 July took up new defensive positions (on the western bank of the river Alolya, near Vodobeg, and further on the line Berezovskoye–Dukhnov). Of course, this position, hurriedly manned with disorganized units, could not stem the pursuing enemy. Already on 11 July, the front was broken through in several places; yet, we frustrated Russian efforts to surround our units. Fighting a continuous rear-guard action, the 15th Division during the night of ll/l2 July retreated across a narrow neck of land between lakes, near Panov.

The Russians penetrated into, the 19th Division's sector through the junction between the 19th and 15th Divisions South of Dukhnov. The 2nd section of the 19th [Latvian numeration: 2nd] Artillery Regiment found itself in a particularly dangerous position. Its route of retreat had been cut by enemy tanks; the unit's antitank guns had no ammunition; simultaneously, the unit was under artillery fire from the rear. Suffering heavy losses, the unit at last broke out. The 15th Artillery Regiment, which retreated together with the 19th Division, also suffered heavy losses. Near Dukhnov, Col. Plensners had an incident with the commander of a VI SS Corps rear guard company, a German lieutenant. Accused of having disobeyed orders, Plensners was arrested and turned over to a military field court. However, the court found that the charges against Col. Plensners were untrue, and released him.

On the morning of 12 July both divisions took up a new position on the line Chernoye - Zvoni - Laptev, some 10-15 km East of Opochka. But already around noon the Russians broke through this position; the fighting lasted all through 12 and 13 July. During the night of 13/14 July our units retreated to the Western shore of the river Velikaya. The retreat was difficult, because there were only two bridges&mash;near Opochka and Krasnogori; the latter had been prematurely blown up by the Germans. The river was high and the current rapid. Many of our units had to wade across shallows, swim across, or cross the river on improvised rafts. On the Western side of the river Velikaya the Latvians fought until 15 July, when all units were obliged to retreat.

The retreat of the 3rd Regiment was particularly tragic. The regiment (including the 1st Battalion of the 4th Regiment and a company of the 15th Sapper battalion), had 500 men, as well as a German battalion of 240 men. The regiment, commanded by Lt.-Col. Aperats, on 15 July started to retreat in the direction of Pokrovskoye (near Zilupe, east of Karsava, on the Latvian-Russian border). The German battalion, which headed the march, lacked maps, and, instead of Pokrovskoye, reached Kopin on the river Isa, around midnight on 15 July 1944. Since the bridge across the river had been destroyed, the force had to swim across, and—at the same time—beat off attacks by strong partisan forces. On the morning of 16 July the group had crossed the river and continued to march North. At Stolbov the exhausted soldiers rested, and at 1 PM, continued to move North, in the direction of Mozuli. At a crossroads the group surprised a Russian battalion (the battle school, as it turned out, of a Russian division), and totally annihilated it, capturing weapons, horse-drawn transport and motorized transport. Having reached Peski, the battle group met renewed resistance and again attacked the enemy. Then, suddenly, 40 Russian tanks appeared over the crest of Mozuli hill; simultaneously, the enemy attacked the group from the rear. After a desperate battle lasting five hours, Lt.- Col. Aperats' battle group was destroyed: 22 Latvian and 6 German officers, and 300 men, were killed; some 300 were taken prisoner. According to reports, the critically wounded Lt.-Col. Aperats shot himself. Posthumously, he was awarded the German Knights Cross of the Iron Cross. As the battle died down, the wounded Maj. Hazners could only gather around him 4 wounded officers and about 60 men. On the night of l6/l7 July, 40 men succeeded in breaking through, and, utilizing swamps and forests, they moved West. It was found, that Aperats' battle group had been in the rear of an entire Red Army corps. Our soldiers, having gone several days without food, ill-armed, and lacking ammunition, had tied the enemy down for an entire day, thus aiding the retreat of the German units, including that of the VI SS Corps. On 17 July, both Latvian divisions crossed the Latvian-Russian frontier East of Karsava.

The retreat organized by the VI S3 Corps had been poorly planned. The infantry was asked to do too much. Within the space of 24 hours, the soldiers had to take up more than two defensive positions; the unavoidable consequence of this was the mixing up of units and the lowering of their capacity to resist. The organization of the rear was unbelievably bad. For example, a section of the 19th Division's staff took over the direction of the regiment's supply vehicles. Due to incorrect orders, the vehicles were pulled back too far and could not fulfill their assigned tasks. The field kitchens of some battalions were in Karsava, Rezekne [Latvia], and even near Riga, while our forces were still fighting at Opochka and Krasnoye. The February, March, and April battles on the banks of the river Velikaya, Southeast of Ostrov, had caused us heavy losses, particularly as regards cadres. The replenishments of the gaps in our ranks (i.e., from the frontier guard regiments), could not replace the losses of officers and NCO's—neither in a tactical and technical sense, nor in morale. During the stabilization period in the Kudevere position, the best NCO's and soldiers were sent to officers schools and NCO courses; they had yet not returned. This explains the relatively poor performance of the Latvian units during the retreat.

Vidzeme, Latvia

On 18 July 1944, general Streckenbach, the divisional commander, met with his regimental commanders in order to decide the fate of the 19th Division. From the Latvians, Col. Lobe (divisional infantry commander), Col. Skaistlauks, Lt.-Col. Taube, Lt.-Col. Kocins, and Maj. Galdins took part in the meeting. In the discussion of organizational questions it became clear, that the division could not be reconstituted on the

lines existing before the 10 July Russian offensive, when each regiment had consisted of three full battalions; the manpower losses were too great. Gen. Streckenbach announced, that for re-forming and training purposes it had been decided to transfer the 15th Division to Germany. The fate of the 19th Division, he said, was an open question; a decision would have to be made. The Latvian commanders should first decide whether their units wanted to participate in the defense of their homeland at all. To the last question, the Latvian commanders unanimously gave affirmative answers. Lt.-Col. Kocins proposed to leave small, heavily armed units in Vidzeme, which, if it came to the worst, could continue a guerrilla war. Col. Lobe stated, that the 19th Division should remain as it was; new reinforcements were needed. The divisional commander agreed, that the divisional form should be nominally retained; the regiments should consist of as many companies as could be handled by the remaining officers. In order that the units would receive tactical tasks commensurate with their true battle strength, the army and corps were advised that the 19th Division had been reduced in strength and for the time being would call itself Kampfgruppe Streckenbach. In order to facilitate the regrouping, the units of the 19th Division were pulled further back (the 1st Artillery Regiment, however, remained in position to support German units). On 20 July, the Division began the march and on 23 July reached the Lubana-Dzelzava region. In a week the regroupment had been accomplished. The regiments were renamed battle groups. The 1st Regiment [Latvian numeration] — Kampfgruppe-bataillon 42. [German numeration]; the 2nd Regiment [Latvian numeration] — Kampfgruppe-bataillon 43. [German numeration]; the 6th Regiment [Latvian numeration] — Kampfgruppe-bataillon 44. [German numeration]. In

official documents the units retained their former names. In reducing the infantry regiments, a part of the men were assigned to the 15th Division; the 15th Artillery regiment and the 15th Sapper Battalion, in turn, were now assigned to the 19th Division. The remainder of the 15th Division, including a small nucleus of officers and NCO's, was moved to the Valmiera-Limbazi region; later, during the second half of August, 1944, they were shipped via Riga to Germany, to be utilized as cadres for the new 15th Division forming there. At this time, changes also took place in the command of the VI SS Corps and the 15th Division took place: Generalleutnant Treuenfeld, who had commanded the Corps only since June, was replaced by SS General Krieger; von Obwurzer replaced the 15th Division's former commander General Heilmann.

On 27 July, the 19th Division was ordered to take up positions on the northern shore of Lake Lubans and the forests lying north of the lake. The German units had been pushed back all along the front and were so frightened, that they actually expected the Russians to cross Lake Lubans itself to attack them.

The 19th Division's strength was as follows. Infantry: 1st Regiment (CO, Maj. Galdins) — six assault companies, a headquarters company, a heavy company with mortars, an antitank platoon; 2nd Regiment (CO, Maj. Stipnieks) — 4 assault companies, a headquarters company, a heavy company; the divisional reserve battalion (CO, Maj. Laumanis) — 3 assault companies and a heavy company; 6th Regiment (CO, Lt.-Col. Kocins) — 4 assault companies, a heavy company, a headquarters company. Artillery: 1st Artillery Regiment (CO, Col. Skaistlauks) — 3 light and 1 heavy sections. This force arrived on 8 August, during the time of the Aizkuja-Cesvaine battles. The 2nd Artillery Regiment (CO, Maj. NN), with 2 light sections, arrived only in the beginning of September, when the Division stood at Tirza. Technical units: The 15th Sapper Battalion (1st lt. Ijabs, CO); the 19th Communications Battalion (CO, maj. Gosepath); the 19th Sapper Battalion (CO, lt.-col. Saulitis) — arrived from Czechoslovakia during the second half of August; finally, the 19th Antitank and 506th Antiaircraft units.

Already on 28 July 1944, the 19th Division took up a 40 km wide position on both sides of lake Lubans, on the line Aizkarkles - Ikaunieki - NW shore of lake Lubans - Zvidziena - Lielpurvi - Licagals - Roznieki; the right flank was manned by the 6th, center—by the 2nd, and left flank—by the 1st Regiment. On 30 July the Russians attacked our left flank and penetrated to Roznieki, defended by German units. The Germans could not halt the enemy; therefore, the 4th company of the 1st Regiment was sent there. It counterattacked and threw the enemy back. On 1 August, the line held by the 19th Division was extended to Barkava. Between companies now there were 0.5 - 1 km wide gaps of stands of unharvested crops. On 3 August, the Russians broke the resistance of the German divisions, took Varaklani and Barkava, and in the afternoon also Aizkraukles and Licagals. The enemy superiority was enhanced by our artillery's complete lack of ammunition. On 4 August, the Russians, after strong artillery preparation, penetrated into the gaps between the companies of the 6th Regiment. Since the enemy had penetrated into both flanks of the Division, it was ordered to retreat to the left bank of the river Aiviekste during the night of 4/5 August. On 5 August, the Russians began to cross the river and established a bridgehead by capturing a bridge defended by a German punishment battalion. Near Meirani, enemy infantry attempted to cross Aiviekste on rafts; our 6th Regiment destroyed them with bazooka fire. Strong enemy infantry and tank forces now assaulted the flank and rear of the 6th Regiment, coming from across the bridge, from the locality of Ubani, along the Western bank of the river Aiviekste; the enemy was attacking in the direction of Meirani and the town of Madona. Utilizing the deep Meirani forest on its right flank and the Olga swamp behind it, it was possible to patch up the Division's exposed flank after a difficult forest battle. Unable to crush the 1st Regiment's defenses at Licagals, the Russians tried to go around lake Lubans, by forest paths, from the North; they hoped to cut the Lubans-Cesvaine highway on the left flank of the 19th Division—and that was the only supply road for the entire division. Although the 1st Regiment repulsed a Russian attack along the highway, the enemy, moving by forest paths, went around the left flank of the 19th Division and reached Dambisi (some 3.5 km North of Lake Lubans). On 6 August, the 2nd Regiment, thrown over there by auto transport, and supported by artillery, after a battle lasting seven hours defeated 2 Russian regiments from 2 different divisions. Still, on the afternoon of 6 August the 19th Division's situation was not good. Our units securely held the positions on the river Aiviekste. The Russians, however, had concentrated strong forces near Cepurites (5 km Northeast of Dambisi) and began a new attack. In order to cut the 19th Division's rear communications, the Russians—continuing their push against Dzelzava and Madona—on 6 August threw 2 divisions North; thus, they hoped to bypass the Lubans forest from the West and take the towns of Cesvaine and Dzelzava. Since neither the [German] l6th Army nor the VI SS Corps had any reserves to throw against both of the Russian wings attacking the 19th Division from the North and the South, the situation could only be saved by a retreat from the river Aiviekste position.

Already on 6 August the 2nd Regiment was ordered to pull back to the Cesvaine region. For this move, the Division had only a single road—the Cesvaine-Lubans highway. Since the 6th Regiment was near Meirani, it had to first get to the highway, skirting the Olga swamp, where its motorized columns bogged down several times. On 7 August 1944 the 19th Division took up new positions on the line Dalgi - Silenieki - Aizkuja - Ataugas - Dravenieki. There, especially in the right wing, began a battle with the Russians, who were attacking on a broad front. Our regiments were placed as follows: Right wing—2nd, center—6th, left wing—1st. Already in the evening of 6 August the 2nd company of the 2nd Regiment came into contact with superior Russian forces near Poteri. When both sides received reinforcements, on 7 August began a struggle on both sides of the road, North and South of Poteri. Both flanks of the 2nd Regiment were exposed. In order to improve the situation, Maj. Stipnieks launched an attack designed to create an unbroken front line. A company commanded by 1st Lt. Butkus took Lejasbulatas. In the afternoon the enemy broke in the forest east of Gaitnieki and Silenieki. An immediate counterattack, led by 1st Lt. Butkus, partly cleared the forest. The 6th Regiment was ordered to attack in the direction of Aizkujas and Silenieki. The attack began on 8 August. The only tie between the 6th and 1st regiments was at Pietnieki; therefore, the brunt of the Russian assaults was directed against this juncture, l½ Latvian companies were attacked by an entire Russian regiment, supported by artillery. Kalnabulatas also changed hands several times in bitter fighting; yet, the 2nd Regiment managed to retain them. The 6th Regiment took Priednieki, Lejiesi, and Abolkalns, but having suffered heavy losses, could penetrate no further; artillery support was lacking. The commander of the 2nd Regiment, in view of his exposed right flank, in the evening of 8 August decided to pull back to new positions West of Bikseri. With this, ended the so-called "Lubans battles." On 9 August, the 6th and 1st Regiment were also pulled back to new positions; on the whole, the front line now stood along the railroad [running between the towns of] Plavinas and Cesvaine. Already on 9 August, the Russians had penetrated to the Cesvaine railroad station, but were thrown back again.

During the "Lubans battles" the Latvian units achieved the impossible. No matter how the Russians tried, the Latvian forces could not be surrounded; indeed, they beat the attacker at the southern end of Lake Lubans (6th Regiment), and at Dambisi anf Valgi (2nd Regiment). The battles at Dalgi, Aizkujas, and Priednieki frustrated the enemy's effort to take the town of Cesvaine, which, if taken, would have let the Russians to (1) surround the Latvian forces in the Lubans area, and (2) open up the road to the city of Cesis—this would have meant that Vidzeme province would have been cut in two, and a wedge driven between the German l6th and 18th Armies (the latter was still fighting in Estonia).

On 10 August, the Russians, supported by strong tank forces and using a hitherto unequaled concentration of multiple guns (the so-called "Stalin organs"), attacked the 2nd Regiment. The regiment repulsed the attack, but the German sapper battalion on its right flank buckled under the pressure. The Russians broke through the main line of defense and threatened to envelop the right flank of the 2nd Regiment. Panic threatened to break out in its ranks, and only through the energetic leadership of Maj. Stipnieks were the units rallied and the enemy stopped.

On 12 August, a new defensive position was formed on the line Cesvaine - Ceplisi - Kurpnieki - Nesaule hill. After the retreat to these positions there was a lull in the fighting, which the Division utilized to replenish losses suffered in the preceding battles. The Field Reserve Battalion, which had taken part in all actions, was renamed the 19th Fusiliers Battalion and sent to Jaunpiebalga for training. Col. Lobe (the infantry commander of the 19th Division) was first sent to Zosen to supervise the training of reserve units, and then to Torn [Germany] as second in command of Latvian construction regiments. There, already on 16 December 1944 he was turned over to a field military court, being accused of collaboration with the Latvian resistance movement.

On 20 August the Russians again attacked the Division's right wing, defended by the 2nd Regiment. A heavy struggle, with luck favoring alternatively both sides, now began. After an extremely heavy artillery barrage the Russians on 21 August continued their attack; the center and the left wing of the 2nd Regiment could not stand the pressure and started to retreat North. The attack also hit the right flank of the 6th Regiment, whose 3rd company also started to retreat. Utilizing this breakthrough, the Russian forces rapidly moved in the direction of Karzdaba. However, thanks to a concentrated curtain of fire from our [depressed] antiaircraft guns, personally directed by the divisional commander Gen. Streckenbach, we surprised the Russians and forced their remnants to retreat. The enemy, because of heavy losses, broke off the attack, and there was another lull in the fighting. Thus ended the so-called Cesvaine-Karzdaba battles. During this all three battle groups received new battalions and discarded the title Kampfgruppe. The grenadier regiments were now 2 battalions strong, had an artillery battery, and sapper and communications platoons. The so-callcd "Ulrich regiment," consisting of a German battalion and Lt.-Col. Birzulis' police battalion, was also tactically subordinated to the division.

On 19 August 1944, a Russian tank force had penetrated from Madona to Ergli, threatening to surround all German forces North of the river Daugava. A counterattack by German mechanized units completely defeated this armored wedge at Ergli, and the threat to Riga was averted. The Red Army, which on 1 August had penetrated to the city of Tukums, was thrown back to the city of Jelgava and Siauliai [Lithuania] by General Schoerner's successful counterattack, begun on 16 August. In the second half of August, the front line in Vidzeme province was: Ergli - Skriveri - Liezere - Karzdaba - Cesvaine - Dzelzava - Gulbene - Lejasciems - [The river] Gauja. Thus, from Liezere to Lejasciems there was a "sack" towards the East; in it, together with other formations of the VI SS Corps, also was the 19th Division.