How did Hāzners become the first former Latvian Legionnaire to be subjected to a U.S. deportation trial in the "hunt for Nazis", accused of being a Holocaust perpetator personally responsible for killing hundreds of Jews?

The appropriate question is not "how"? but "why?"

Hāzners was a prominent Latvian leader, member of multiple Latvian cultural and Latvian representative to multi-national anti-Soviet activist organizations, employed by the CIA as a fact-gathering resource, Radio Free Europe broadcaster, and general secretary of the Daugavas Vanagi (Hawks of the Daugava), the veterans' welfare organization Latvian Legionnaires. He was such a thorn in the side of the Soviets that the Latvian SSR KGB staged annual domestic anti-Hāzners propaganda campaigns. Hāzners and the Vanagi became the lightning rod for Soviet anti-émigré wrath, their identities conflated into unity of Latvian moral depravity.

Daugavas Vanagi

Latvian Legionnaires founded Daugavas Vanagi in 1945 while incarcerated as POWs at the Zedelgem POW camp. It is well known today how the Germans subjected Russian POWs to horrific conditions. But few are aware Allied guards at Zedelgem shot Latvian POWs for sport until they were told the Latvians weren't Nazis.

In the seventy-nine years since, the Daugavas Vanagi have remained true to their mission where the families of veterans are concerned, and have also taken on the task of preserving and bolstering Latvian cultural and history awareness at home and abroad. However, someone reading sensationalized exposés of Nazis hiding in America would find these unfounded accusations instead:

- Daugavas Vanagi is an organization "composed of the Latvian SS officers and government ministers who oversaw the Final Solution in their country"1

- Daugavas Vanagi is a "council of Latvian war criminals based in West Germany"2

- "In each of those Eastern European countries, the German SS set up or funded political action organizations that helped form SS militias during the war. In Hungary, for example, the Arrow Cross was the Hungarian SS affiliate; in Romania, the Iron Guard. The Bulgarian Legion, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN ), the Latvian Legion, and the Byelorussian (White Russian) Belarus Brigade were all SS-linked. In each of their respective countries, they were expected to serve the interests of the German Nazi Party before and during the war.3

- many Daugavas Vanagi leaders "had served as the Nazis’ most enthusiastic executioners inside their homeland"4

- officerships in the Latvian Legion were rewards for loyal and tenacious service to the Nazis5

The KGB's "Daugavas Vanagi — Who Are They?"

These accusations come straight from Soviet propaganda. As Holocaust scholar Andrew Ezergailis explains6:

The Soviet propaganda version [of the Holocaust in Latvia], on the other hand, is a different kettle of fish: like an abstract collage it was pasted together piece by piece: cannibalizing both the Nazi ["Germanless"] and the survivor narratives. The Soviet version is encapsulated in the 1961 pamphlet Daugavas Vanagi, Who are They?, by Paulis Ducmanis, a Nazi era, Berlin-educated, journalist.

This pamphlet was a collage of extended passages from [Max] Kaufmann’s memoirs [published in 1947]7 that were combined with material from the 1961 show trial of the 18th Police Battalion. Conceptually the Soviet version differed from the Nazi one, if we penetrate their ideological armor, only in one particular: the Soviets peppered their text with the words “fascism” and “nationalism.”

Of the three “Germanless” variants, it was the Soviet one that gained the greatest currency and influence on Nazi hunters and Holocaust historians the world over. The Soviets used its diplomatic reach to distribute the KGB literature throughout the world. Naming of names was the bait that hooked the Nazi hunters in the West on the Soviet/KGB pamphlets. The pamphlet became a kind of a handbook for Nazi hunters in the West and was the source of the famous Wiesenthal lists that were circulated to a number of Western governments during the 1980s. It took several trials, exhaustive investigations, and millions of dollars to discover that the KGB had given the westerners a run around. In as much as Ducmanis, who originally compiled these names, had done it with total disregard for truth, no successful prosecution could result by pursuing the names on the lists. The first major case in which the KGB and survivors’ accounts were tested was that of Vilis Hāzners in 1979. The OSI (the Office of Special Investigations) picked up Hāzners’ name, but no evidence, from KGB literature. It was up to the hapless American prosecutors to hunt up witnesses and establish credible evidence. They thought they found the witnesses and evidence among the Jewish survivors in Israel8 and the West. The evidence that they garnered from them was not better or worse than one usually gets from eye witnesses — full of errors, misidentifications, and contradictions. Hāzners’ defense attorney Ivars Bērzinš made short shrift of the witnesses, thus persuading the trial judge of Hāzners’ innocence. The trial records show that the prosecution would have been better off without calling any eye-witnesses at all.

The question, then, is how did Daugavas Vanagi — Who Are They? come to form the backbone of a scholarly narrative9 of the Holocaust in Latvia which persists to this day?

Dancing With the KGB

Gertrude Schneider's 1971 trip to Latvia marked the penetration of anti-Latvian Soviet propaganda into the mainstream. Wined and dined by the Soviets, dancing with the Latvian cultural minister (a KGB officer), showered with KGB-manufactured materials—books, brochures, and transcripts of fabricated show trials purporting the U.S. had become a den of Latvian Nazi collaborators and Holocaust perpetrators, Schneider, herself a Holocaust survivor of the Rīga ghetto, returned home appalled and energized to root out the war criminals the Soviets had identified to her.

Schneider's gathering of Rīga ghetto memories formed the basis of her 1973 doctoral thesis: THE RIGA GHETTO, 1941 - 1943. Her thesis and derivative books over the years are widely acknowledged as seminal works on ghetto life.

Unfortunately, for accounts of the Holocaust at the ghetto gates and beyond, Schneider's thesis relied heavily upon on the Soviet propaganda she had recently brought back with her from Soviet-occupied Latvia. For example:

While the Germans provided expert guidance, it was the Latvians who did the "dirty" work. Obergruppenfuehrer Friedrich Jeckeln, the Hoehere SS und Polizeifuehrer Gruppe Nord, who was attached to all the Einsatzgruppen with his mobile killing units, credited the Latvians with "strong nerves for executions of this sort," at his trial after the war.a

a Avotins, Dzirkalis & Petersons, Daugavas Vanagi (Riga, 1963) p. 24.

"Avotiņš, Dzirkalis, and Pētersons" are the the collective pen name of the aforementioned Paulis Ducmanis, a pre-war sports reporter turned Nazi propagandist turned Soviet propagandist, and his anonymous KGB masters. There is no evidence or record that Jeckeln made this or any other of the three most cited "truths" about the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Latvia:

Holocaust scholar Andrew Ezergailis connected personally with Ducmanis, who confirmed that Daugavas Vanagi was a book of lies concocted, by its profuse naming of names, to maximize credibility.

- that Latvians killed a large, indeterminable number of Jews before the Germans arrived in Latvia;

- that Latvians had more nerve for killing Jews than the Germans—per the quote above; and

- that Jews were brought to Latvia from the West "because the Latvians had created the proper conditions for it."

Neither Jeckeln's translator at trial or a full review of his trial records during a brief period of post-Soviet accessibility contain any indication Jeckeln said anything at all about Latvians, other than being subjects of Himmler's disdain.

Jeckeln at his Soviet trial for atrocities in the Baltic states (Ezergailis, Holocaust in Latvia)

Jeckeln at his Soviet trial for atrocities in the Baltic states (Ezergailis, Holocaust in Latvia)If we compare Schneider's thesis to her updated 2001 Journey into Terror: Story of the Riga Ghetto, given what we know now—and in 2001—about Ducmanis's fiction, how has the passage of time impacted Schneider's narrative?

In other words, while the Germans provided the expert guidance, the Latvians only too willingly did the "dirty" work. At his trial after the war, Obergruppenfuehrer Friedrich Jeckeln, the Hoehere SS und Polizeifuehrer Gruppe Nord who had taken over the job after Stahlecker's demise, credited the Latvians with “strong nerves for executions of this sort.” [no citation given]

Schneider's account is virtually unchanged from nearly three decades prior except for embellishing Latvian eagerness to kill their neighbours and eliminating her inconvenient citation to the KGB's invention.

And what of Prof. Dr. Andrew Ezergailis, the Holocaust scholar who also—initially—fell victim to Paulis Ducmanis' master-work promoting the "Germanless" Holocaust—never expecting to some day share cognac with him in Rīga, even visit him at his home? From Journey:

There is, furthermore, a pseudo-scholarly work by a Latvian-American,b which was supposed to show the complicity of the Gentile Latvians in the murder of both native and foreign Jews, but instead became an apologia.

b Andrew Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia 1941-1944: The Missing Center. (Riga: The Historical Institute of Latvia; published in association with the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, 1996).

Schneider denigrates Ezergailis' scholarship on the Holocaust in Latvia and insinuates he is an ethnically motivated Holocaust apologist. Ezergailis is the widely acknowledged pre-eminent authority on the Holocaust in Latvia and the work Schneider cites is the seminal work in the field.10 Unfortunately, it appears Schneider would rather impugn Ezergailis's motives and scholarly integrity than confess she was similarly swept off her feet by Ducmanis' masterwork—after dancing with the KGB at a soirée in Latvia.

We understand now why Ezergailis, in his retrospective, laments the loss of a friendship and colleague.

KGB materials mainstreamed and amplified

Schneider describes the Nazi invasion and immediate horror in her thesis and in Journey. We have highlighted passages in her more recent Journey and analyse following our paragraph-by-paragraph comparison across the decades:

On July 1, 1941, the Germans entered Riga. The final chapter of its Jewish community, numbering 40,000 men, women, and children, began. The Latvians made the Germans' job an easy one, by committing unbelievable atrocities against the Jews. Many Latvians joined the SS, in order to be part of the German machine.

On July 1, 1941, the Germans marched into Riga, the capital of Latvia, and the final chapter of Riga's Jewish community, numbering forty thousand men, women, and children, began. 1Many Latvians helped the German invaders by committing unbelievable atrocities against the Jews and even joined the SS in order to be part of the Nazi hierarchy.

On July 7, only one week after having come to the city, Einsatzgruppe A, one of the four main groups employed in effecting a final solution in the eastern territories, organized a pogrom in Riga, and reported that 400 Jews were killed. Pictures were taken to show how the natives took "self-cleansing action." In a report to Himmler, Dr. Franz Stahlecker, the official in charge of Einsatzgruppe A. stated that no other outbursts took place in the Baltic states.c

| c | Reichssicherheitshauptamt IV-A-1, Operational Report USSR 15, July 7, 1941, No. 2935. Stahlecker to Himmler, October 15, 1941, L 180. |

On July 7, less than a week after their arrival in the city, Einsatzgruppe A organized a pogrom in Riga and reported that four hundred Jews had been killed. 2As evidenced by photographs, the actual slaying was done by Latvians and not Germans. The 3Nazis described this outrage as a “self-cleansing” operation. In his report to SS Chief Heinrich Himmler, Dr. Stahlecker, the head of the group, stated that no other operation of that nature had taken place in his domain.

He may not have known about conditions in the Central Jail, the site of brutal murders, or the Riga Police Prefecture, presided over by Roberts Stiglics. It is possible also that he forgot about the Perkonkrusti, the Latvian fascist organization, who, under the able leadership of Sturmbannfuehrer Victor Arajs, a Latvian, murdered at least two-thousand Jews during July alone, concentrating on the well-to-do, so as to confiscate their property.d In the Great Synagogue of Riga, a gang led "by that same Victor Arajs and Herbert Cukurs, burnt alive several hundred Jews, chiefly women and children.e

| d | J. Silabriedis & B. Arklans, Political Refugees Unmasked (Riga, 1965) p. 21. |

| e | Ibid., pp. 49 - 56. |

4Stahlecker must have been referring only to operations organized by the Germans. As it turned out, 5they did not have to make an extra effort, considering the conditions that normally prevailed at Riga's Central Prison, called Zentralka, a site of the most brutal murders, or at the Riga Police Prefecture, which was presided over by Roberts Stiglics. Stahlecker might have 6overlooked the Perkonkrusts. The Latvian Fascists, who, under the able leadership of Sturmbannfuehrer Victors Arajs, a Latvian, murdered at least two thousand Jews during July and August 1941 alone. The Perkonkrusts looked for and concentrated on the well-to-do, in order to be able to confiscate their property. In the Great Synagogue of Riga, a gang led by that same Victors Arajs, 7aided by Herbert Cukurs and Vilis Hazners, incinerated alive several hundred Jews, chiefly women and children.f

| f | Victors Arajs, who is no longer alive, was awaiting trial at the time the first edition of Journey into Terror was published. For more than three decades he lived under his wife's maiden name in Germany. Cukurs was executed in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1965, by a detachment of Israelis who called themselves "The Avengers." 8Hazners lived in baronial splendor near Albany, New York, insisting that the charges against him were part of a communist-inspired plot. |

The Riga press did its best to encourage the populace in their hatred against Jews. Articles appeared such as one printed July 11, 1941, aptly titled "The Jew - Our Destroyer." It ended: "The sins of the Jews are great. They wanted to destroy our nation - therefore, as a nation of culture, they must die."g

| g | Tevija, the main Latvian newspaper, issue of July 11, 1941. The editor was Pauls Kovalevskis, vice manager was Arturs Kroders. The owner of the paper met Himmler in Berlin, in 1942, and assured him that there was no longer a Jewish problem in Latvia. Quoted in Daugavas Vanagi. p. 21. |

The 9Riga press did its best to fan the hatred of the Latvian populace for the Jews. Articles appeared such as that printed on 10July 11, 1941, most fittingly entitled “The Jews-Source of our Destruction.” The article ended with the statement that because the Jews had sought to destroy the Latvian nation, they could not be permitted to survive as a national or a cultural entity; therefore, all the Jews would have to die.h

| h | 11Tevija, the main Latvian newspaper, July 11, 1941. Its editor was Pauls Kovalivskis [sic.]; Arturs Kroders was the manager. The 12owner of the paper met Himmler in Berlin in 1942, and assured him that there was no longer a "Jewish Problem" in Latvia. |

Everything Schneider writes about the Holocaust in Latvia is cited to KGB propaganda except for a single reference to Stahlecker's report.

A more complex issue is that Stahlecker's report itself documents not the spontaneity the theater he himself organized, complete with German cameras to record the "spontaneous" slaughter by locals. The charade of the "Germanless Holocaust" had already been planned and discussed in May, 1941:

- one month prior to Germany's invasion of the USSR;

- two months prior to Göring's request to Heydrich for a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in Nazi-controlled territories; and

- eight months prior to the Wannsee Conference.

Personal German correspondence back to Berlin confirmed, for example, that it was a unit of a dozen German police that cleansed the Lithuanian countryside of Jewry, not Lithuanian locals. Regarding German newsreels of the "Germanless" Holocaust unfolding in Rīga, we can quote from Joseph Grigg's news report published in London, June 1, 1942 (our emphasis):

This slaughter went on for days and there was even an official German newsreel of squads shooting Jews in the streets of Riga. The Nazi commentator describes the scenes as the vengeance of “the infuriated Latvian populace against the Jews,” but a remarkable feature was that the “Latvians” all wore German army helmets.

Propaganda as Holocaust scholarship

Readers of Schneider's Journey into Terror have no clue that Schneider removed the inconvenient citations to KGB propaganda which she included in her 1973 thesis.

No one was launching the Holocaust just on the news the Nazis were coming. The Germans immediately established total control and disarmed the populace. There is absolutely no dispute over the collaborators the Nazis subsequently organized, such as Arājs Kommando. However, there is no documentary evidence for the most frequent accusation that Latvians spontaneously killed their Jewish neighbors before the Nazis even arrived, even suggesting collaborator formations had already been created, judging by their German, not Latvian, names in anticipation of Holocaust participation, or, as Schneider states here, that droves of Latvians immediately lined up for jobs to kill Jews.

Nor could any Latvian, not even the Nazis' criminal collaborators, join any "Nazi hierarchy": neither Nazi party nor Allgemeine-SS. Latvia was occupied. Even "collaborators" collaborated on terms totally dictated by the Germans. There was no autonomy under Nazi occupation.

Regardless of illegally conscripted11 or volunteering, the two Eastern Front Latvian Legion divisions were front-line military units formed in 1943 initially from non-Holocaust collaborators already serving in combat under the Wehrmacht. They swore no allegiance to Nazism, and as even Efraim Zuroff stated emphatically in 2012 on Latvian television, they had no role in the Holocaust.

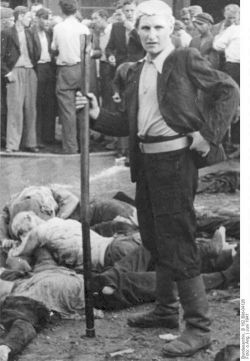

The Holocaust in eastern Europe is documented to have been planned—prior to the Nazi invasion of the USSR—to appear spontaneous and Germanless. That included staging "locals" standing by stacks of bodies, portraying them as having, typically, bludgeoned men, women, children, and infants to death in the most horrific manner. Fortunately for historians, some of these photos accidentally include showing the Germans managing their Holocaust theater production, including hiring and dressing in uniforms local drunks as stooges. How naïve—or blinded by bias—does one have to be to trust the veracity of Nazi photographs and newsreels purporting the Nazis were bystanders to the Holocaust?

Stahlecker confirms the charade in his very report Schneider cites:

"It had to appear to the outside that the indigenous population itself reacted naturally against the decades of oppression by the Jews and against the terror created by the communists in its recent history, and that the indigenous population carried out these first measures of its own accord."

Horrific mass slaughters, such as those at Rumbula, were methodically executed by Jeckeln's hand-picked men. (Schneider never retracted the propagandist lie in her writing that Latvians did the slaughter because the Germans didn't have the stomach for it.) The Germans entrusted industrialized human extermination only to themselves.

There was no "self-cleansing." This portrayal was the hallmark of Berlin's plan to mask German responsibility for the genocide of the Jews. Indeed, in Lithuania, where similar accounts were circulated, a witness confirmed in a letter to Berlin that it was a squad of a dozen German policemen who slaughtered Jews going to village to village, and not the local Lithuanians as the witness had been informed earlier, via official reports, in Berlin. The witness wrote it would look very bad for Berlin's image if the truth—apparently widely known locally—were to surface.

As compared to her thesis, Schneider accentuates the trope of the Germanless Holocaust, that the Germans controlled only their own actions, that they allowed armed Latvians to roam free on their own to perpetrate anti-Jewish actions. On the contrary, there was no independent Latvian action. Even the Nazi-organized Arājs Kommando had to check their non-automatic arms out in the morning and check them back in at night—or risk being shot by their German masters.

Schneider continues with the myth that Latvians were in charge even while Latvia was occupied, having just suggested Stahlecker spoke only for German actions and not those at the Central Prison under Roberts Štiglics, the Rīga prefect. She appears unaware that Stahlecker had his office at the Prison and had brought Štiglics to Rīga and installed him in his position. Štiglics was no more than another "Sicherheitsdienst" ("SD") operative. Everything Holocaust-related that took place at the Rīga Central Prison was subordinated to Stahlecker from the start. Schneider echoes the factually unfounded contentions of Bernard Press and Max Kaufman, who contend there was a central Latvian authority independently organized and operating in Rīga following the Nazi invasion. As contended even by the U.S. government in its brief against Hāzners, this supposed authority was organized within hours of the Soviet departure, preceded by a call to arms on the radio by Voldermars Veiss and the killing of Jews before the Germans arrived—all a complete fiction, including the alleged "broadcast." That false storyline includes the additional allegation that the Nazis permitted the Latvian authority to continue operating after the occupation was established because Nazi and Latvian aims—the wholesale murder of Jews—were the same. Alan A. Ryan, Jr. has vehemently insisted that the Department of Justice did not use unsolicited Soviet materials—despite the DOJ parroting blatantly false Soviet propaganda verbatim in court briefs and introducing KGB propaganda materials as evidence via the witnesses possessing them. With the passing of the Professor Ezergailis (1930–2022), we may never see Ducmanis's bequeathed personal list of duped Nazi-hunters.

"Political Refugees Unmasked," cited, is another KGB propaganda tome, similar to "Daugavas Vanagi—Who Are They?"

Involvement of the Pērkonkrusts in the Holocaust is hearsay. Even KGB records—documented to contain fabricated anti-Latvian show trial evidence such as word-for-word identical "testimonies" from multiple witnesses—indicate that only perhaps four individuals of Arājs unit, 300-500 during the Holocaust, and some 300 tried and convicted in Soviet courts immediately after the war, were former members of the fascist Pērkonkrusts. The Ulmanis regime had jailed the Latvian fascists and exiled their leader Gustavs Celmiņš before the war. As Latvian ultra-nationalists, former Pērkonkrusts members represented a threat to the prior invading Soviet regime. Most were hunted down and killed or deported to Siberia. Nor were relations with the invading Nazis much better. Celmiņš did return to Latvia, accompanying the Germans as a translator, and there were some Pērkonkrusts members who aided the occupation authoring propaganda. However, their organization was already outlawed by August, 1941 for their nationalist—including anti-German—views. Tellingly, rather than organize to kill Jews, Celmiņš petitioned the occupational authorities for the right to organize armed Latvian units to pursue the Russians on the Eastern Front.12 As the Nazi occupation took hold, even the leader of the pre-war Latvian fascist Pērkonkrusts cared only about securing the Eastern Front against the Soviets. The Nazis eventually jailed Celmiņš for his pro-Latvian nationalism.

Regarding Arājs's "leadership," we have mentioned the checking out and in of arms—the Germans directly supervised all actions of their criminal collaborators. No collaborators organized or operated independently. All offers of "collaboration" were refused; the Germans managed collaborators only on their own terms. What Arājs did lead was his men's drinking binges while also operating a lucrative black market of items the Germans had authorized them to steal from Jews. Arājs's men were ordered to wear civilian clothes while rampaging through Jewish property to mask German culpability and appear to be the local populace run amok.

Schneider accuses Hāzners of being a leading Holocaust perpetrator. (Both the KGB officer, later defector, dancing with Schneider in Rīga and Schneider both confirmed he had mentioned Hāzners to her by name.) Schneider's thesis was her opening salvo launching her life-long campaign against Latvian Nazis.

One Hāzners witness identified him as being a major when herding Jews into the cathedral to be burned; that was only Hāzners's rank at the end of the war — and in the Soviet propaganda materials he possessed and which the DOJ entered into evidence. Meanwhile, testimony at trial proved Hāzners could not have been present. Nevertheless, Schneider's denunciation of Hāzners nearly 20 years after Hāzners's vindication (1981, Journey into Terror published in 1979; this is from the 2000/2001 "new and expanded" edition) indicates she never lost faith in the KGB propaganda and bogus show trial materials she brought back from the USSR. There was no possibility of Latvian innocence.

Regarding Pērkonkrusts, both Soviet trials of Arājs Kommando members and that of Arājs in Germany confirmed minimal — perhaps three or four — Pērkonkrusts in the Kommando.

Lastly, Herberts Cukurs, assassinated by the Mossad as the alleged "Butcher of Riga" was not in Riga, either, when the Gogol Street synagogue was burned (July 4th), arriving only later on July 14th. Schneider is mistaken on both accounts.

CIA documents prove the Soviets launched a concerted campaign to discredit Hāzners and other prominent Latvian émigrés, Daugavas Vanagi, Who are They? and a full length "documentary" film about their atrocities both being released in 1963—followed by the KGB's specific mention of Hāzners, by name, to Schneider in 1971, launching the "Latvian Nazi" witch-hunt. Moreover, the author of the allegations and the KGB agent who handed the allegations to Schneider both subsequently and independently confirmed the Soviet plot and fabrications. Lastly, Hāzners lived in a modest farm-house with a view of Lake Champlain—Schneider's evocation of "baronial splendor" is the instantiation of her own rage and indignation.

There was no "Rīga press," as if it were somehow Latvian. The only "press" published was that produced, controlled, and censored by the Nazi authorities and their quislings. Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda was on the whole a failure in its attempt to incite the Latvians. That Latvia had been the only European country in which anti-Semitic literature was banned, that pre-war Latvia had been a welcoming transit point for Jews escaping Hitler, are far more accurate measures of Latvian attitudes. Indeed, as preserved in Nuremberg trials records, reports back to Berlin after the invasion bemoaned the Latvians' apathy to the Nazi's anti-Semitic agitations, in line with anti-Semites denouncing Latvia as a "Jewish country" before the war because of the positive image and role of Jews in Latvian society.

The conclusion of the article mentioned, facsimile.

The conclusion of the article mentioned, facsimile.Anti-Semitic articles appeared starting with the very first issue of the occupational Nazi newspaper Tēvija ("Fatherland"), published the same day the Germans entered Rīga with Red Army still retreating. Jews, "bastards," the English, the French, were all denounced. The article mentioned was written as a first-person opinion piece, signed "Albatross," believed to have been the paper's first "editor," Arturs Kroders. Kroders was a historian and political activist. Unfortunately and unsurprisingly, his memoirs conclude before the events of the war, so the true nature of Kroders' relationship with Tēvija is likely to never be known, however, we do know his fiery nationalism brought him into conflict with the Germans, who dismissed him.13

As to the article content, the representation quoted per Daugavas Vanagi: Who Are They? and cited in Schneider's thesis, is nearly accurate (our translation follows, our emphasis):

"He [the Jew] will earn [his] bread in the same manner as have our labourers. The sins of the Jews are overly grievous: they wished to annihilate our nation, therefore they must die as a cultural nation. [That is, Judaism can no longer exist as a culture and Jews must be assimilated into the secular working class. — Ed.]

"So states and testifies a person, who, hair now turned grey, had not cared in the least regarding the Jewish question. Now he comprehends the nature of the Jew, and that there must be no Latvian compassion. Albatross."

Schneider's relates the passage as written in her thesis, while subsequently in Journey she removes the quotation and purports it called for killing all Jews which, while grossly anti-Semitic, it clearly did not. The dead cannot continue to earn their daily bread.

Tēvija ("Fatherland") was a Nazi occupational authority newspaper published in the Latvian language. It arrived and departed with the Nazi occupation. It was no more the "main Latvian," meaning a Latvian enterprise, paper than was Cīņa (the proletarian "Struggle"), published under the Soviet occupation. Indeed, as soon as the Russians were gone, the Latvians launched the newspaper Brīvā Zeme ("Free Country"), which the Germans immediately shut down and replaced with Tēvija.

The notion that Tēvija, a newspaper created and run by the Nazi occupational authorities, was "owned" by a Latvian, as implied, is fantastical. The paper was produced by the Nazi Reichskommissariat Ostland propaganda department. The publisher was Ernests Kreišmanis. Tēvija listed a number of Latvian "editors" during the course of the Nazi occupation: Arturs Kroders, Andrejs Rudzis, Pauls Kovaļevskis, finally Jānis Vītols. Censorship duties, requiring German and Latvian fluency, were assigned to Ernst Eduard von Mensenkampff, editor of the former Rigasche Rundschau ("Rīga Observer"). Latvian authorities had shut the paper down in 1934 for having too many Nazi connections.14

It is worth noting that "there was open conflict between the Latvian editors and their [German] supervisors. On 5 February 1942, editor [sic.] Ernests Kreišmanis questioned the second-class status of Latvians, demanding to know why Latvians received fewer rations than Germans. LVVA/f. P-70, apr. 5, I. 3, 227.15"

The trip by Kreišmanis to Berlin is another Ducmanis fabrication.

Schneider's embellishments over time of Latvian participation and anti-Semitism reflects a wider trend in Holocaust scholarship targeting the peoples of Eastern Europe as the "true" enablers and perpetrators of the Holocaust, worse than the Nazis themselves.16 Alan A. Ryan, Jr.'s allegation of 10,000 Nazis hiding in the United States—debunked in the OSI's self-review of its past activities17—lives on as well. Disturbingly, even the OSI's disavowal states that if so many still believe the 10,000 number for no other reason than to have heard it endlessly repeated because it came from Ryan in his widely acclaimed Quiet Neighbors), then there must be some basis belief persists.18

| 1 | Anderson, S. and Anderson, J.L.. Inside the League: The Shocking Exposé of how Terrorists, Nazis, and Latin American Death Squads Have Infiltrated the World Anti-Communist League, Dodd, Mead, 1986, page 36, ISBN: 9780396085171. LINK |

| 2 | ibid., page 285. |

| 3 | Bellant, R.. Old Nazis, the New Right, and the Republican Party, South End Press, 1991, page 4, ISBN: 9780896084186. LINK |

| 4 | Simpson, C. and Miller, M.C.. Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Destructive Impact on Our Domestic and Foreign Policy, Open Road Media, 2014, ISBN: 9781497623064. LINK |

| 5 | "The Latvian extremists [Vanagi] held on tenaciously during the Nazi occupation, however, and many were rewarded with posts as mayors, concentration camp administrators, and — most frequently — officers of the Latvian Waffen-SS division sponsored by the Nazis" ibid. |

| 6 | Caune, A. and Stranga, A. and Vestermanis, M. and Latvijas Vēsturnieku komisija. Holokausts Latvijā: starptautiskās konferences materiāli, 2004. gada 3.-4. jūnijs, Rīga, un 2004.-2005. gada pētījumi par holokaustu Latvijā, Latvijas vēstures institūta apgāds, 2006, ISBN: 9789984601595. LINK |

| 7 | Elsewhere in Ezergailis's essay: "Among the insupportable assertions one can name the following: (1) that prior to the German occupation there was a Latvian center that planned the killing of the Jews; (2) that an uncounted number of Jews were killed by Latvians prior to the German occupation; (3) the most absurd of all, is that while Latvians were killing Jews the Germans saved them. Like Latvians and the state of Latvia ought to face the Latvian role in the Holocaust, the surviving Jews ought to face the stubborn fact that Latvia was an occupied country. They ought to show an understanding of the system that Germans imposed within their zones of sovereignty. To me the three above assertions that some surviving Jews view as unquestionably true, appear as basic misjudgements of the Nazi regime. Max Kaufmann’s Die Vernichtung der Juden Lettlands, published in 1947, was the first, and still is the most extensive memoir by a Holocaust survivor in Latvia, and is one that contains the three misapprehensions. It is remarkable that years have not mellowed these assertions but, if anything, they have rigidified them." |

| 8 | Israeli authorities introduced photos of Hāzners (and others) as Nazi war criminals. They then coached and drilled witnesses to identify Hāzners as the person in photographs once they thought they might have recognized him. One issue in the INS case, but not the one causing it to fall apart as is contended, is that the "trial" exhibits were copies, not the originals, and that the exhibit of photographs was also rearranged during the proceedings. |

| 9 | David Cesarani (1956–2015) even contended that “much of the material it [Daugavas Vanagi, Who are They?] presents has been verified independently" — when the author, Ducmanis, has confessed the work is a fabrication. Cesarani, David. Justice Delayed, 2001, page 304. |

| 10 | Raul Hilberg's assessment of Ezergailis' work: “This massive study...spares no detail ....Ezergailis is no youngster and he spent many years gathering the facts and writing the text. He has complete command of the literature and the trial records. His research took him to many archives. Needless to say, he could read the Latvian sources with full understanding. He is painstakingly objective and he tries to the utmost to be precise. “What he wrote is limited in scope but not minor in importance. Latvia affords a window to the critical topic of the initiation of the final solution. The Jewish victims there were not only local inhabitants but also deportees from the Reich. The Riga massacres in the late fall of 1941 were, after Odessa and Kiev, the largest in Europe. More important, however, must be our recognition of the fact that Ezergailis represents the next wave of Holocaust research: the indepth exploration of a particular aspect or territory. In that sense he is a pioneer and his work serves as a model.” |

| 11 | By the end of the war, the Nazis had forced every Latvian male less than 40 years old into military service. |

| 12 | Kangeris, Kārlis. Latviešu leģions – vācu okupācijas varas politikas diktāts vai latviešu “cerību” piepildījums?, , BALTIJAS REĢIONA VĒSTURE 20. GADSIMTA 40.– 80. GADOS, page 68, accessed 13 July 2016. LINK |

| 13 | The Nazis were strongly suspected of having assassinated Viktors Deglavs, one of the senior pre-war Latvian army officers (along with Aleksandrs Plensners who eventually was the senior officer of the Latvian Legion), who had come into direct conflict with Stahlecker shortly after the invasion. The Nazis cleaned house after Deglavs' murder; for Latvian efforts against the Soviets to continue, Plensners was forced to accede to how the Germans wished to organize. Kroders was fired after devoting too much space in Tēvija to Deglavs and Plensners, to Deglavs' funeral and to commemorative articles about him. The July 24th issue, including articles regarding Deglavs' funeral, was Kroders' last. |

| 14 | Matthias Schröder, Deutschbaltische SS-Führer und Andrej Vlasov 1942–1945, Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2001, pp. 80–4 |

| 15 | Wingfield, N.M. and Bucur, M.. Gender and War in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe, Indiana University Press, 2006, ISBN: 9780253111937. LINK |

| 16 | Simon Wiesenthal described Eastern Europeans as more evil than the Nazis for having collaborated. “The guilt of the Nazi helpers in the occupied territories, especially the Eastern countries, is, in my opinion, greater than the guilt of the (German) Nazis,” Wiesenthal said.—Special to the JTA, Wiesenthal Says U.S. Had Names of Nazis Before They Entered Country, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 28 November 1978, accessed 15 January 2016. LINK |

| 17 | Judy, Feigin. The Office of Special Investigations: Striving for Accountability in the Aftermath of the Holocaust, 2006, page v. |

| 18 | "The 10,000 figure has enduring significance, however, because it has been widely reported, to the extent that people believe it, it unfortunately suggests that the number of cases handled by OSI — approximately 130 — is de minimus." ibid. |